Má and loops

Má … nó …

You can make choices in your program! We use the word má (meaning “if”) to make a check, and then to make a choice with the result of that check. Look at the following program:

aois := 14

má aois >= 13 & aois <= 19

scríobh('Is déagóir thú')

nó

scríobh('Ní déagóir thú')This program checks if aois is between 13 and 19. If it’s true, it writes ‘Is déagóir thú’ (You’re a teenager). If it’s not true it writes ‘Ní déagóir thú’ (You’re not a teenager).

We can use this structure again and again, like this.

má ainm == 'Oisín'

scríobh('Oisin, tar liomsa go Tír na nÓg')

nó má ainm == 'Fionn'

scríobh('Dia duit Fionn, an bhfuil Oisín anseo?')

nó

scríobh('Tá brón orm, Níl aithne agam ort')- If

ainmis equal to ‘Oisín’ this writes ‘Oisin, tar liomsa go Tír na nÓg’ (Oisín, come with me to Tír na nÓg). - If

ainmisn’t equal to Oisin, it then checks ifainmis equal to ‘Fionn’, if it is it writes ‘Dia duit Fionn, an bhfuil Oisín anseo?’ (Hello Fionn, is Oisín here). - If

ainmwasn’t Oisín or Fionn, then it writes ‘Tá brón orm, Níl aithne agam ort’ (I’m sorry, I don’t know you)

Use { and } to make a group of instructions.

má x == 6 {

scríobh(x)

scríobh(2 * x)

} nó {

scríobh(x)

scríobh(3 * x)

}You can use ma and no if you can’t type ‘á’ or ‘ó’.

Loops

We use loops when we need to do something again and again.

Le .. idir ..

When we know how many times we want to do something, we can use this loop

le i idir (0, 10)

scríobh(i)This program writes every number between 0 and 10, it doesn’t write 10 because the loop stops before the last number.

You can put another number in the brackets to change the step between numbers. For example:

le i idir (0, 10, 3)

scríobh(i)This writes 0, 3, 6, 9 as the step size is 3.

Example

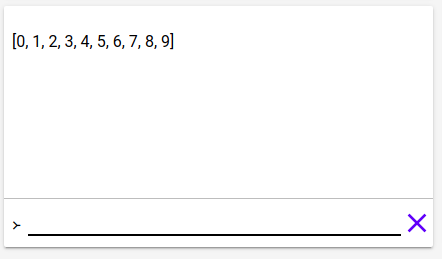

We will use a loop to make a list of every number between 0 and 10.

liosta := []

le i idir (0, 10) {

liosta = liosta + [i]

}

scríobh(liosta)Run that code and look at the console.

Nuair-a

There is a simpler loop available too, called nuair-a (which translates as “when”).

At first the loop checks the term after the nuair-a, if it’s true, it follows the instructions in the loop, and it goes back to the start. If it’s not true, it breaks out of the loop. It does this over and over until the check is false.

In the following example, it goes through the loop 5 times, and then x == 6, specifically x < 5 is not true, and with that, the loop is finished.

x := 0

nuair-a x < 5 {

scríobh(x)

x = x + 1

}We get 0, 1, 2, 3, 4.

bris & chun-cinn

In both of those loops, le idir and nuair-a, you can use the instructions bris and chun-cinn. bris does exactly what it says, it breaks out of the loop. If Setanta follows this instruction, it stops the loop and it continues after the loop.

x := 0

nuair-a x < 100 {

má x == 10

bris

scríobh(x)

}This loop writes 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9, and then x == 10 and we break out of the loop.

chun-cinn does something different. chun-cinn goes directly to the top of the loop, and it starts with the next one. For example:

le i idir (-10, 10) {

má i < 0

chun-cinn

scríobh(i)

}This loop writes 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 9 8 9, because for each i < 0, the chunn-cinn instruction is followed, and we start with the next number.

Big example

We have an example now that uses everything we’ve seen, loops, má, variables, the stage ….

Run this code and look at the stage:

dath@stáitse('gorm')

>-- Na súile

ciorcalLán@stáitse(200, 200, 50)

ciorcalLán@stáitse(400, 200, 50)

dath@stáitse('dearg')

x := 100

y := 400

>-- Béal

le i idir (0, 40) {

dron@stáitse(x, y, 20, 20)

x += 10

má i < 10

y += 3

nó má i < 20

y += 1

nó má i < 30

y -= 1

nó

y -= 3

}

>-- srón

dath@stáitse('oráiste')

cruthLán@stáitse([[300, 270], [270, 350], [330, 350]])

Now go to the next tutorial: Actions (gníomh)